It’s no secret that the food delivery business is booming during this global lockdown. In Germany, Delivery Hero reported a 92% increase in revenue. In the US, Uber Eats saw 30% user growth at the end of the March.

Unfortunately, Uber Eats (and other food delivery services) is even more unprofitable than ride sharing. In this week’s article, we discuss why that is, and explore potential ways food delivery companies can become profitable. We also showcase an example of a profitable company in this space (whose share price outpaced Google, Facebook, Amazon and Apple in the past decade).

The unprofitability of the food delivery business

The growth of Uber Eats during the global lockdown has been a lifeline for the company (considering Uber’s core ride-sharing business saw an 80% drop in global number of rides in Q1 2020). Unfortunately for Uber, Since Uber Eats is even more unprofitable for the company than ride sharing, acceleration in this business means even faster cash depletion.

Unlike ride sharing, where Uber shares the fee paid by the passenger with the driver (two-way split), in the food delivery space, the fee that the customer pays is split between the driver, Uber and the restaurant (three-way split). Furthermore, Uber has to spend more on driver incentives in the food delivery business.

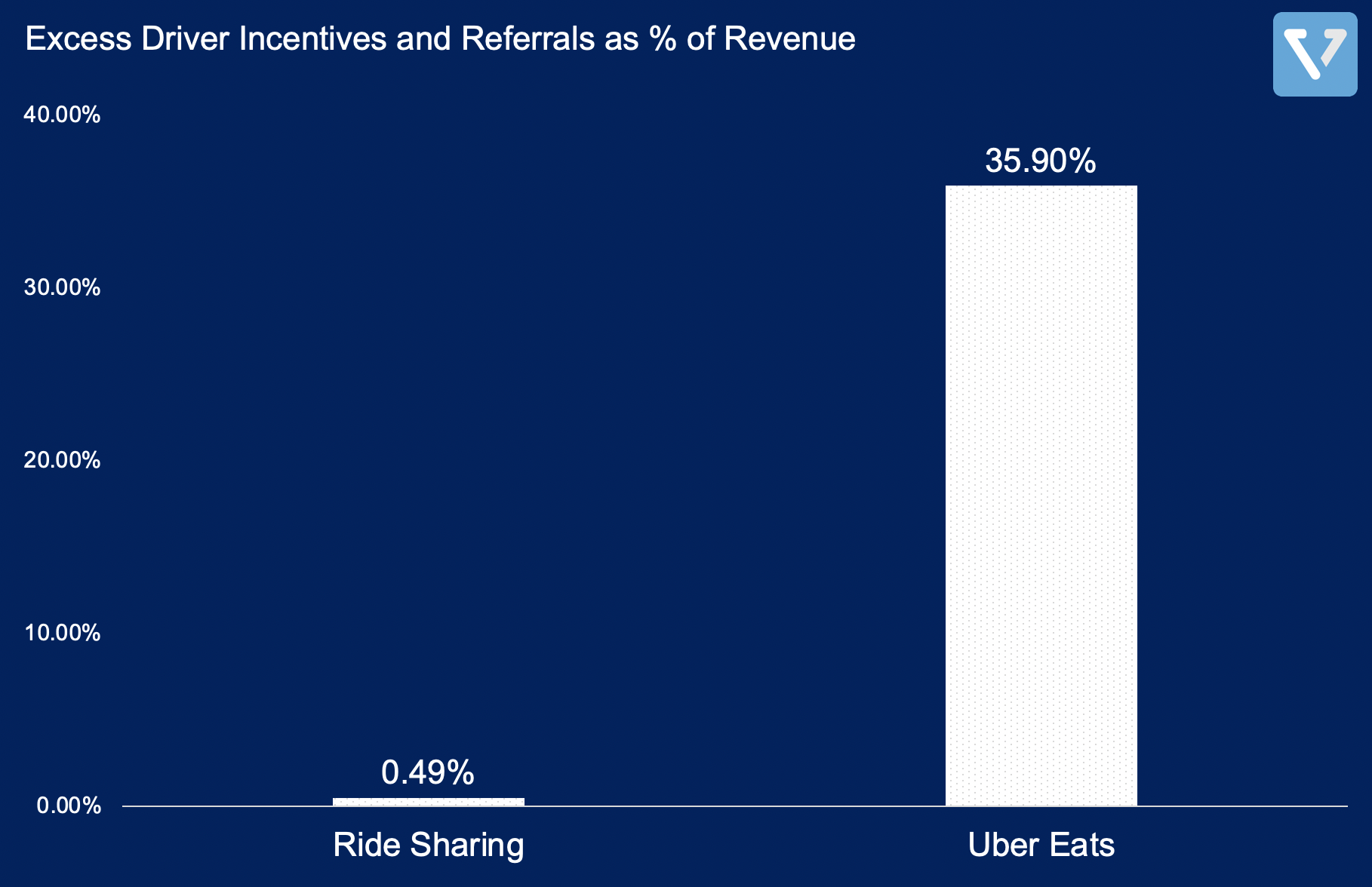

In Q1 2020, the Uber Eats business line spent 35.90% of its revenue towards excess payments and driver incentives (vs. 0.49% for ride sharing) – in other words, Uber Eats spends US $1.36 in driver incentives and referrals for every US $1 of revenue a driver generates. See Figure 1.

As a result, the more orders Uber Eats serve, the faster the company loses money.

Figure 1: Excess driver incentives and driver referrals as % of revenue for both ride sharing and Uber Eats. Note that excess driver incentives refers to payments that the company makes to its drivers that exceed the cumulative revenue from said drivers. Data from the company filling

So, how can one be profitable in the food delivery business?

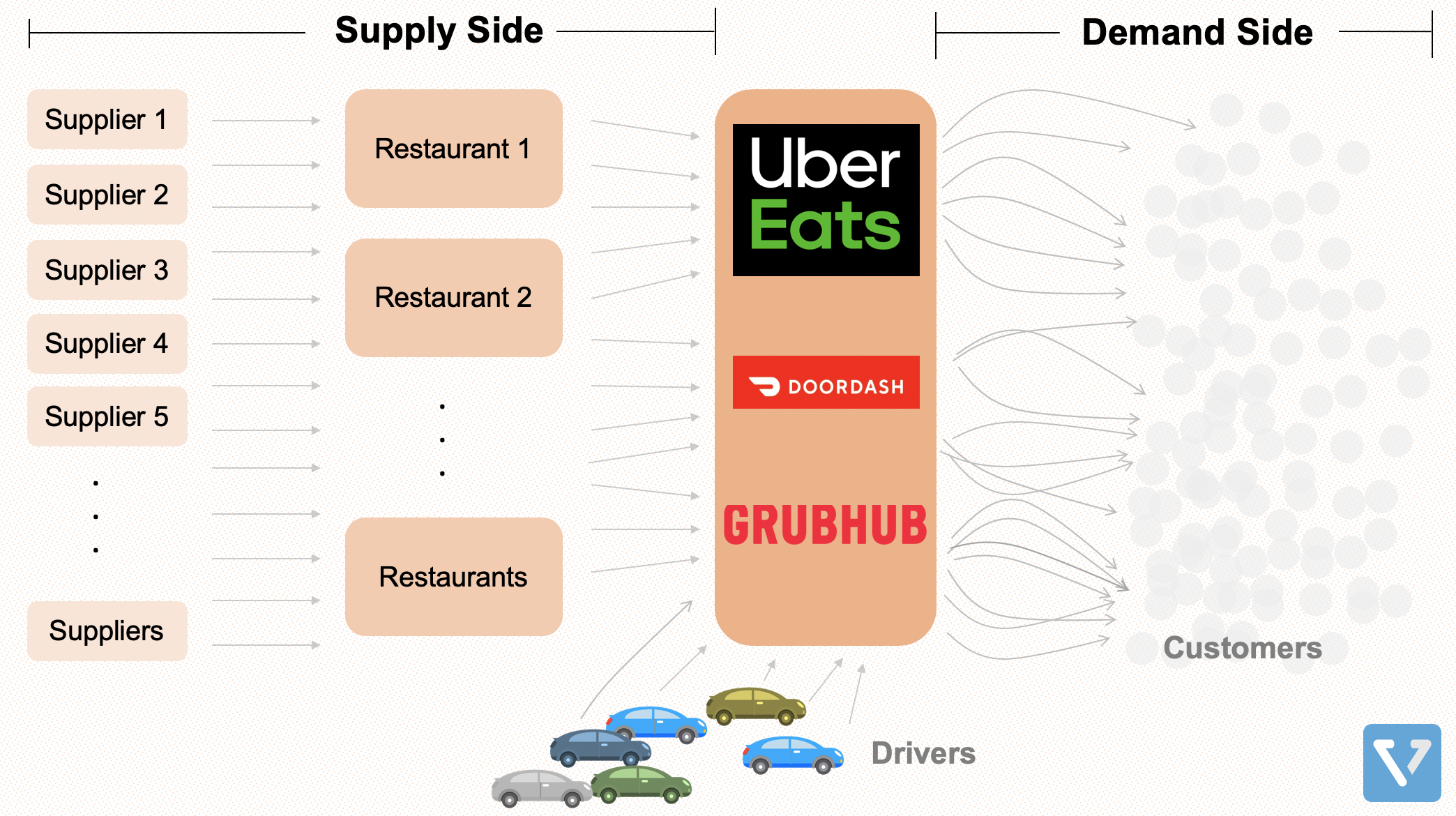

Before we answer that question, let’s look at the value chain (Figure 2) of Uber Eats (note that this is applicable to Grubhub (ticker: GRUB), DoorDash, and Uber’s other competitors in the food delivery space). These technology-driven food delivery platforms are “aggregators†of demand. They stand between the restaurants and their customers. They also compete with one another to get as many users as possible, Having a significant number of users on the app helps these companies onboard more restaurants, which in turn provide liquidity in the marketplace that attracts drivers.

Figure 2: Value chain of a typical food delivery business

The problem with this value chain is that there are competing interests between the different actors in this ecosystem:

- The restaurants want to get as much business as possible, so they sign up on all available food delivery platforms (this is called multi-tenanting)

- This means that for Uber Eats and its competitors, supply side inventory is undifferentiated (users can generally get any restaurant from any app) – weakening the defensibility of their businesses

- This leads to users to constantly switching between different apps – forcing these food delivery companies to continue to subsidize user acquisition

- Meanwhile, the drivers have no loyalty and, similar to the restaurants, will deliver for multiple applications. Again, this means that the food delivery companies have to constantly spend to make sure that they have enough drivers on the platform

The result is a no-win situation for the food delivery apps and especially the restaurants. Most restaurants operate on very thin margins. They cannot afford to pay the delivery companies that often charge them a percentage of order value plus advertising fees. On top of this, food delivery companies charge delivery and service fees to the customers.

Consolidation

One way for these food delivery businesses to increase their margins is to reduce multi-tenanting for both the restaurant and the driver. They can do this by consolidating. This reduces the options for the customers and drivers, decreasing the need to spend so much on incentives.

This is the reason Uber is interested in acquiring Grubhub. Although the two have not been able to agree on a price. The consolidation trend can also be observed globally: Delivery Hero (a German-based food delivery company) purchased Woowa Brothers as a strategic move to expand across Asia.

Change the value chain

Another option is to play a different game. Domino”s Pizza (ticker: DMZ) is actually one of the first technology-driven food delivery companies. The company struggled in the late 2000’s, but was able to turn the ship around, building technological capabilities with a business model that enabled its share price to outpace the growth of S&P 500, Google, Apple and Amazon over the last decade.

Figure 3: Domino’s share price growth has outpaced some of the biggest tech companies in the world

So, what is so different about Domino’s business model? At its core, the company is a food delivery business delivering only one thing: pizza. We say that the company is a food delivery company because Domino’s owns only 5.6% of stores in the US and owns zero international stores. The Domino’s stores that are not owned by the company are operated by franchises. In India, Domino’s stores are operated by Jubilant Foods.

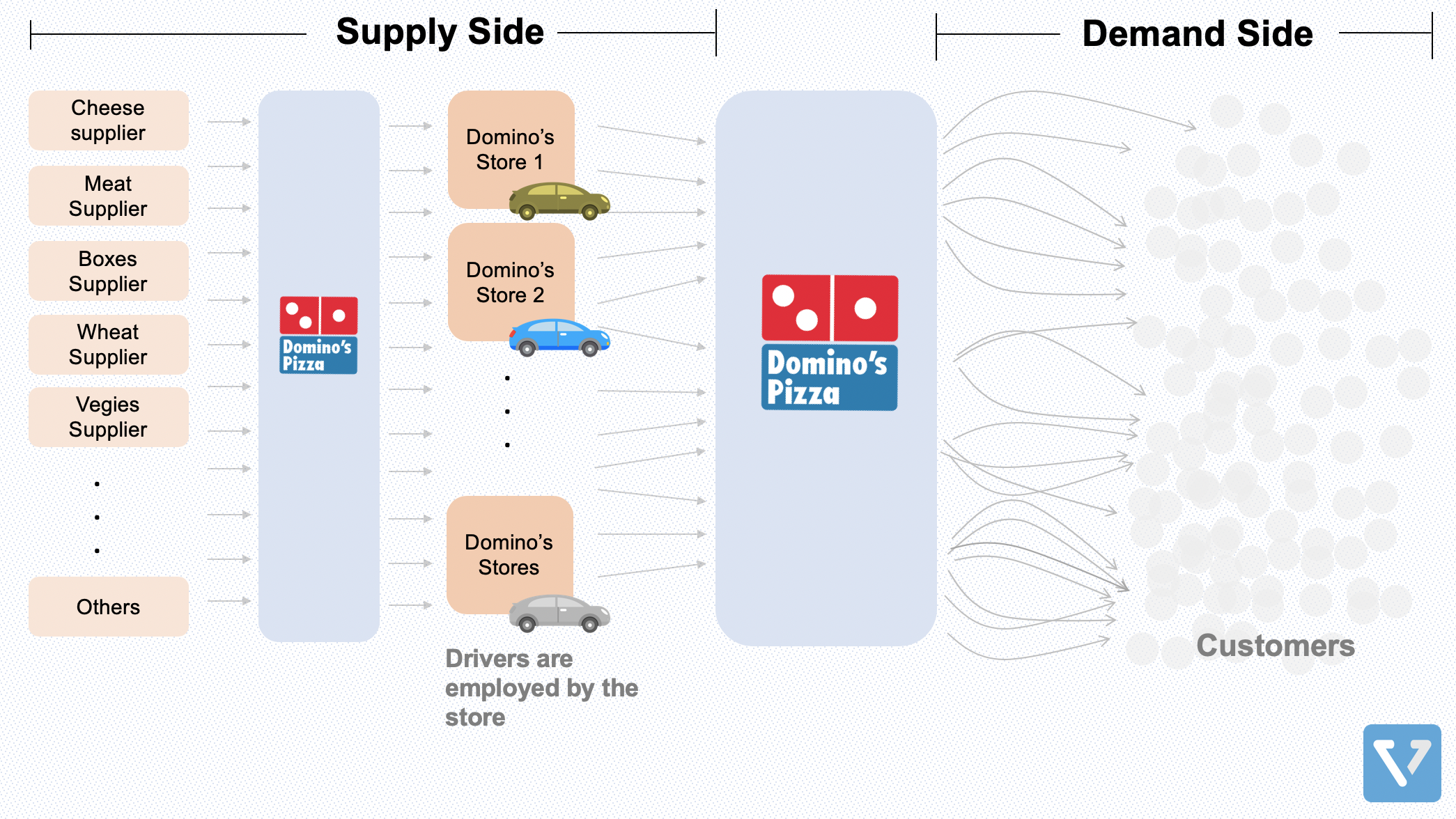

Similar to the food delivery apps, Domino’s aggregates demand, standing between the restaurants and the customers. But unlike food delivery apps, Domino’s stranglehold in the value chain is not just on the demand side, but also on the supply side. See Figure 4.

Figure 4: Domino’s value chain

In Figure 4, anytime an arrow passes through the Domino’s box (light blue), the company generates revenue:

- On the supply side, the company negotiates with suppliers and then sells supplies, raw materials and equipment to its franchise stores. This translates to lower costs and lower price volatilities in raw materials for the store owners since Domino’s is much larger and has negotiating power against the suppliers. For the company, this creates standardization that helps quality control and generates revenue. In Q1 2020, Domino’s made US $512 million (or 59% of revenue), but had a margin of only 11.5%.

- On the demand side, Domino’s provides the store owners marketing, distribution and technology capabilities. If you order from the Domino’s app – your order will automatically be routed based on where you are located. As a customer, you do not really have a relationship with the individual Domino’s stores. On this side of the equation, the company extracts revenue from franchise fees and royalties (5.5% in the US and ~3% internationally, which are much lower than the rate of food delivery apps). Revenue from the demand side is about 30% of Q1 2020 revenue, but is almost pure profit.

As a result, not only is Domino’s profitable, the store owners are as well. There are key differences between the pure technology food delivery companies and Domino’s.

- The stuff they sell. Domino’s only sells pizza. Pizza is by far the most popular food in the US. So Domino’s (and its franchisees) can gain from economies of scale.

- Domino’s value chain is only a two-sided marketplace. Unlike on Uber Eats, where drivers are individual contractors that constantly switch on different apps (and therefore require constant additional incentives), drivers in the Domino’s ecosystem are employed by the store. Thus, the company does not have to spend on extra driver incentives.

The playbook of vertically integrating into the supply side is now being employed by a multitude of startups in the form of cloud kitchens (or ghost kitchens). Cloud kitchens are commercial kitchens occupied by numerous restaurants that share space and resources. They can reduce start up cost and rent (by purchasing/renting large buildings in less trafficked areas). These spaces are typically used by restaurants that only serve food delivery apps (you cannot sit and eat in cloud kitchens).

One of the biggest players in this space, having raised more than US $400 million, is a company called Cloud Kitchen, started by Travis Kalanick (co-founder and former CEO of Uber). But Travis’ company does not have control over distribution. Recall that for Domino’s, its entrenchment in the supply side is what enables it to capture high margin value on the demand aggregation side. But the supply side revenue itself has low margins.

In terms of vertically integrating to the supply side, food delivery apps in India have taken the lead. The two leading food delivery apps have aggressively entered the cloud kitchen space: Swiggy has 1000 cloud kitchens facilities in India, while Zomato has more than 700.

Closing thoughts

To summarize, one way for Uber Eats to improve its margins is by consolidation, Another is to vertically integrate and build out its own cloud kitchen (as Swiggy and Ola are doing). No doubt that this undertaking will be extremely expensive and will take many years before it reaches critical scale.

Alternatively, Uber should just buy Domino’s. Currently, Domino’s has a market cap of US $14 billion. Uber has about US $9 billion in cash. Conceivably, it can raise the funds necessary to complete the transaction. This may help Uber accelerate vertical integration on the supply side, leveraging Domino’s supply chain expertise and international footprint.